The History and Future of Third Parties In America

2024 presents a historic opportunity to challenge America's two-party system.

The Forward Party promises it is taking a novel approach that can bring an end to our increasingly dysfunctional two-party system, but Americans remain deeply skeptical of a third party’s electoral prospects.

A look into America’s history with third parties reveals an unmistakable pattern, one that independents and third party advocates should take note of heading into 2024.

The Forward Party received over 20,000 new members upon the announcement of its recent merger with two similar pro-reform groups. Skepticism of third parties in general, however, dominated the reaction from media outlets.

The New York Times published an opinion titled “Why Andrew Yang’s New Third Party Is Bound To Fail.” An opinion from the Washington Post allowed that “A third party could be successful. But probably not this one.”

Less than a year after its launch, it is unlikely that much of the party’s future is set in stone. In order to get a holistic view of the new party’s future prospects, it must be compared and contrasted with third party movements of the past and present.

Such a view uncovers a pattern which new parties have followed since the mid-19th century, one that Independents and Forwardists should be aware of. Americans who lived in the days of Theodore Roosevelt and Calvin Coolidge saw third parties rise and fall like a Whac-A-Mole.

Below the surface of American history rests an obscure history of outsider movements aimed at ending the two-party duopoly.

I. The Libertarian and Green Parties

The Libertarian and the Green parties are the most prominent modern third parties, with nearly 700,000 members and 250,000 members, respectively.

Former Representative Justin Amash, elected in 2010 as a Republican, switched his party affiliation to Libertarian in 2020 and proceeded to decline a run for re-election. Amash was the party’s first national official, although he was not elected as a Libertarian.

The minor parties contend that restrictive ballot access laws and the perception of wasting your vote are unfairly preventing them from competing, and they are right.

Amid the pandemic, ballot access laws grew only more restrictive. For example, New York passed a law that tripled the number of signatures required for ballot access from 15,000 to 45,000.

The minor parties are thus trapped in a cycle of pouring energy into gaining ballot access for candidates who won’t have a chance of being meaningful competitors once they get on the ballot.

Both parties have devoted substantial resources to national campaigns in the hopes that they could lead a national movement and overcome these systemic barriers.

The Forward Party’s plan, as it appears, rests on two goals: passing electoral reform in the states that allow citizens to initiate ballot measures and electing a slate of local Forwardist officials, starting in 2024, out of approximately 500,000 offices across the country. These local offices include boards of education, finance, and police, city councils, conservation commissions, etc.

Through a focus on changing the system rather than competing electorally to overcome a system that has been rigged against them, Forwardists’ plan diverges from those of modern third parties.

II. The Reform Party

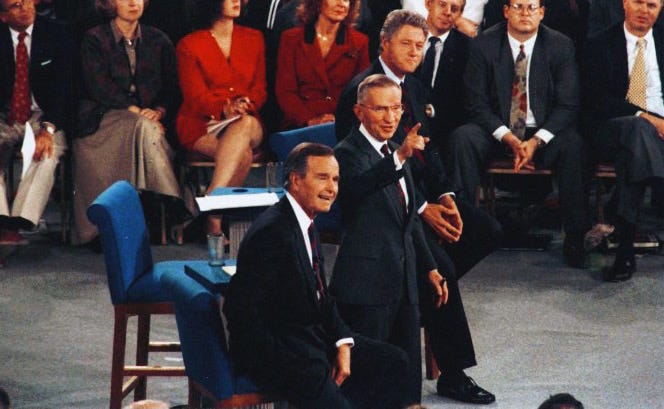

30 years ago, the 1992 presidential election saw a billionaire outsider win nearly 20 million votes against major party candidates.

In June 1992, Ross Perot even led President George H.W. Bush and Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton in the polls. His momentum, however, was crushed by disillusionment among his staff and the suspension of his campaign in July.

Perot re-entered the campaign one month before election day and benefited from participating in the debates, yet the suspension of his campaign proved to be a critical mistake. He earned nearly 19 percent of the popular vote with no electoral votes.

Three years after his initial campaign, he founded the Reform Party and announced a second campaign in 1996. The attention he received from media outlets and voters was muted compared to his initial run, and he was not included in the debates this time around. Perot earned 8 million votes or 8 percent of the popular vote in 1996, a laudable achievement, but one that failed to establish a viable third party.

After Perot’s 1996 run, no Reform Party candidate earned 1 percent of the vote again.

Approaching a third party from a top-down growth perspective means requiring the electoral success of the individuals at the top of the party before they can work to grow the party itself. This approach is both high-risk and high-reward, and none who have tried in modern history have seen the reward.

The Reform Party was built around Perot’s presidential ambitions. When his 1996 campaign failed, so too did the party.

Andrew Yang and Perot are similar in that they both initially viewed running for president as the best way to help the country, but Yang has different objectives in establishing the Forward Party now than he did in his 2020 campaign.

III. The American Independent Party

24 years before Perot’s outsider campaign, the far-right American Independent Party (AIP) was established and won 5 southern states in the 1968 presidential election.

1968 saw great political upheaval with the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy, as well as growing public resentment over the Vietnam War. The Civil Rights Movement divided Americans, and the AIP emerged as a political force to uphold segregation and white supremacy.

The party’s nominee, Alabama Governor George Wallace, ran on a platform of supporting states’ rights to segregationist policies, law and order, and bringing an end to the Vietnam War. Though Wallace’s core support came from segregationist voters, there were Americans who were deeply disillusioned with their government and were open to the idea of his outsider status.

In an environment that saw popular desire for new political choices, the AIP was able to emerge as an insurgent and seized upon political instability in pursuit of their segregationist agenda. The former Vice President Richard Nixon won a decisive electoral college victory, although Wallace won 10 million votes and 46 electoral votes.

The AIP ultimately fizzled before splitting in 1976. Their central support for segregationist policies left it scorned by many Americans. Their electoral strategy was similar to Perot’s: a hail-Mary attempt to change everything from the top.

IV. The States’ Rights Democratic Party

20 years before the AIP’s attempts to contest the 1968 election, South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond led a short-lived segregationist party known as the States’ Rights Democratic Party, or the Dixiecrats, who attempted the same plan.

In 1948, President Harry Truman ordered the desegregation of the US military, prompting southern Democrats to storm out of the party’s convention in protest. Thurmond ran a campaign with the goal of throwing the election to the House and eliciting concessions from the winner on states’ rights to segregationist policies.

The Dixiecrats were less successful than the AIP, winning 4 southern states and 39 electoral college votes. The striking similarities between the efforts of the two parties, however, is worth noting.

V. The Progressive and Socialist Parties

24-36 years before the Dixiecrats’ right-wing insurgency, America saw the rise and fall of three left-wing parties.

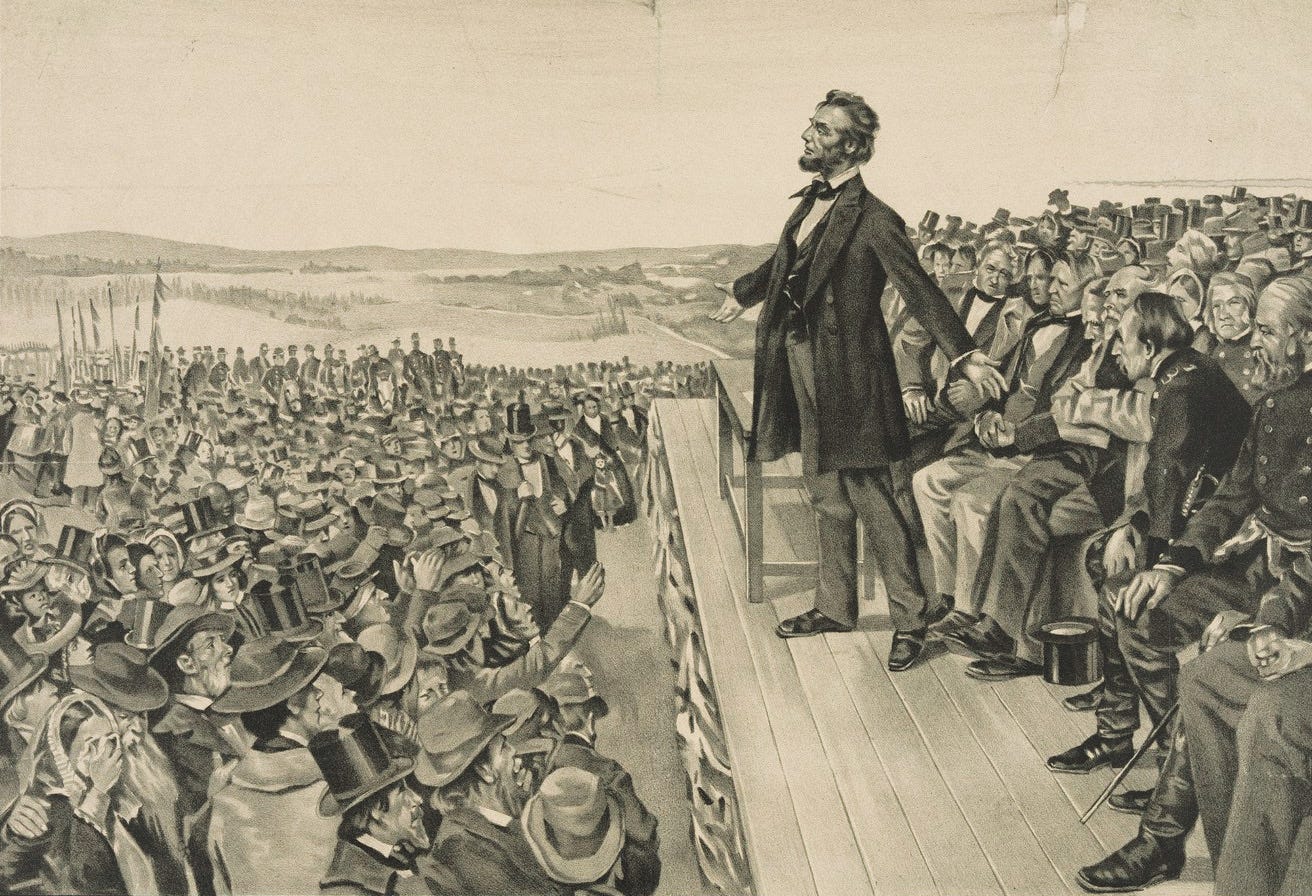

The 20th century in America began with newly re-elected President William McKinley’s assassination in September 1901. His vice president Theodore Roosevelt finished three and a half years of McKinley’s term before winning a full term in his own right.

A champion of progressive politics, Roosevelt oversaw an administration that dramatically expanded the national parks system, established the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), broke up the largest railroad monopoly and regulated the largest oil monopoly.

Roosevelt retired in 1909 a powerful man. He was regarded as a highly influential leader, the American people loved him, and he had the honor of handing off power to his vice president and chosen successor, William Taft.

By 1912, however, the former president’s attitude had changed. He was dissatisfied with what he perceived as a drift away from his original progressive vision by President Taft, and he challenged the incumbent for the Republican nomination.

When his effort to challenge Taft in the Republican primary failed, the Progressive Party, colloquially known as the Bull Moose Party, was launched in an effort to send Roosevelt back to the White House. The party earned second place in the popular and electoral vote, a feat that has yet to be repeated by a third party since. Roosevelt carried six states while his former vice president carried only two.

However, Roosevelt’s Progressive Party acted largely as a vehicle for his candidacy, and it fell apart in the years following his 1912 run.

Eugene Debs, a former representative in the Indiana state House and a prominent socialist, earned a notable 6 percent of the vote in 1912 with the Socialist Party as well. Debs ran for president with the party five times—once while in prison for denouncing America’s participation in World War I—yet their best performance came during the four-way election of 1912.

Debs’ Socialist Party reached a degree of success in the early 20th century, electing two members to the U.S. House and several dozen to state legislatures. The downfall of the party came amid President Woodrow Wilson’s crackdown on anti-war sentiment, although membership had already declined as a result of the party’s opposition to the war effort for several years.

The president passed through Congress the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 with the intention of rooting out foreign interference and insubordination in the military. In 1918, Debs was arrested under the Sedition Act following a speech in which he urged Americans to resist the draft. He was sentenced to ten years in prison, although his sentence was commuted by President Warren Harding three years later.

The Socialist Party’s activity had been further disrupted by the U.S. Postmaster General’s refusal to allow the party’s newspapers to be delivered by the Postal Service. By 1922, the party had only a handful of elected officials scattered around the country.

The left-wing, anti-war party’s experience differs from other third party movements as a result of wartime circumstances and a government crackdown on the party’s operations.

Its membership had already fallen as a result of its opposition to the war, although Wilson’s use of federal power ensured that the party would never succeed.

In 1924, a desire for a third party among American progressives crystallized once again.

Republican President Calvin Coolidge, inaugurated in 1923 upon the death of President Harding, was famous for his devotion to libertarian ideals. Frustrated with what they perceived as two conservative choices from the major parties, a new Progressive Party emerged in 1924 that nominated Wisconsin Senator Robert M. La Follette.

The party ran on a pro-labor, pro-nationalization and anti-imperialism platform, drawing support from a similar coalition to Roosevelt’s party and Debs’. Coolidge won a full term in a landslide, La Follette carried only his home state of Wisconsin, and the Progressive Party fizzled with the end of his campaign.

In a now-familiar story to third party enthusiasts, the two Progressive parties of the early 20th century failed because they were tied to the success of one person at the top. They devoted energy to the success of the candidate, not the party. When the candidate failed, so too did the party.

The Forward Party’s bottom-up approach and focus on electoral reform again puts their strategy in contrast with the Progressive parties of 1912 and 1924.

VI. The Populist Party

A short 20 years before America’s trio of left-wing uprisings, labor advocates saw hope in a populist third party that, for a short time, wielded national political power.

A group known as the Farmers’ Alliance—a broad political coalition of farmers from across the country—rose to prominence amid an emerging perception among Americans that the major parties were both too conservative. In 1890, the group successfully elected 8 members to the House and 1 member to the Senate.

2 years after reaching the national halls of power, the group founded the Populist Party. From 1890 to 1900, the Populists would go on expand their national ranks and elect several governors across the country.

At the party’s peak of national electoral success in 1896, they held 22 seats in the House and 5 seats in the Senate. The new party was founded by James Weaver, a former representative from Iowa, and Thomas Watson, a representative from Georgia.

Weaver launched a campaign for president in 1892—the same year the party was founded—calling for free coinage of silver and public ownership of new innovations including railroads and telephones. Supporters of free silver advocated for an unlimited amount of silver to be coined into currency, dependent on demand. Proponents of bimetallism sought to tie monetary value to both gold and silver.

Some criticized the policy as inflationary, though the early 1890s were characterized by deflation and a depression. The Populist Party viewed free silver as a way to combat severe wealth inequality that had persisted throughout the Gilded Age.

The 1892 election saw Republicans nominate President Benjamin Harrison for re-election while Democrats re-nominated former President Grover Cleveland, whom Harrison had ousted from the White House four years earlier. Harrison and Weaver both supported bimetallism while Cleveland stood for the gold standard. In the end, Cleveland won the election and became the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms.

Weaver won 5 western states and 22 electoral votes with 9 percent of the popular vote—with the support of Eugene Debs—though it was both the first and last time the Populists would impact a presidential race.

Ahead of the 1896 election, the party grew factious and within 6 years, they had lost all of their seats in Congress. The story of the Populist Party is comparable to that of the Socialist Party, which also saw a limited degree of success in national elections. Neither was able to build a foundation that lasted more than ten or twenty years.

The mistake made in this case was the party’s decision to join forces with a major party just four years after its founding. The Populists did not have enough time to stake out an identity that separated them from the major parties.

Forwardists today debate whether the party should seek to work alongside the major parties where it can or if it should remain focused on its independence from the two-party system. The 130-year old lesson of the Populists is that outsiders today should prioritize their independence from the two major parties.

Speaking to his own experience on the 2020 campaign trail, Andrew Yang explained that associating himself with the Democrats immediately drove a segment of the population to tune him out.

VII. The Liberal Republican Party

20 years before the lightning-fast rise and fall of the Populist Party, the Democrats chose to endorse a third party candidate in the hopes of defeating an incumbent Republican president.

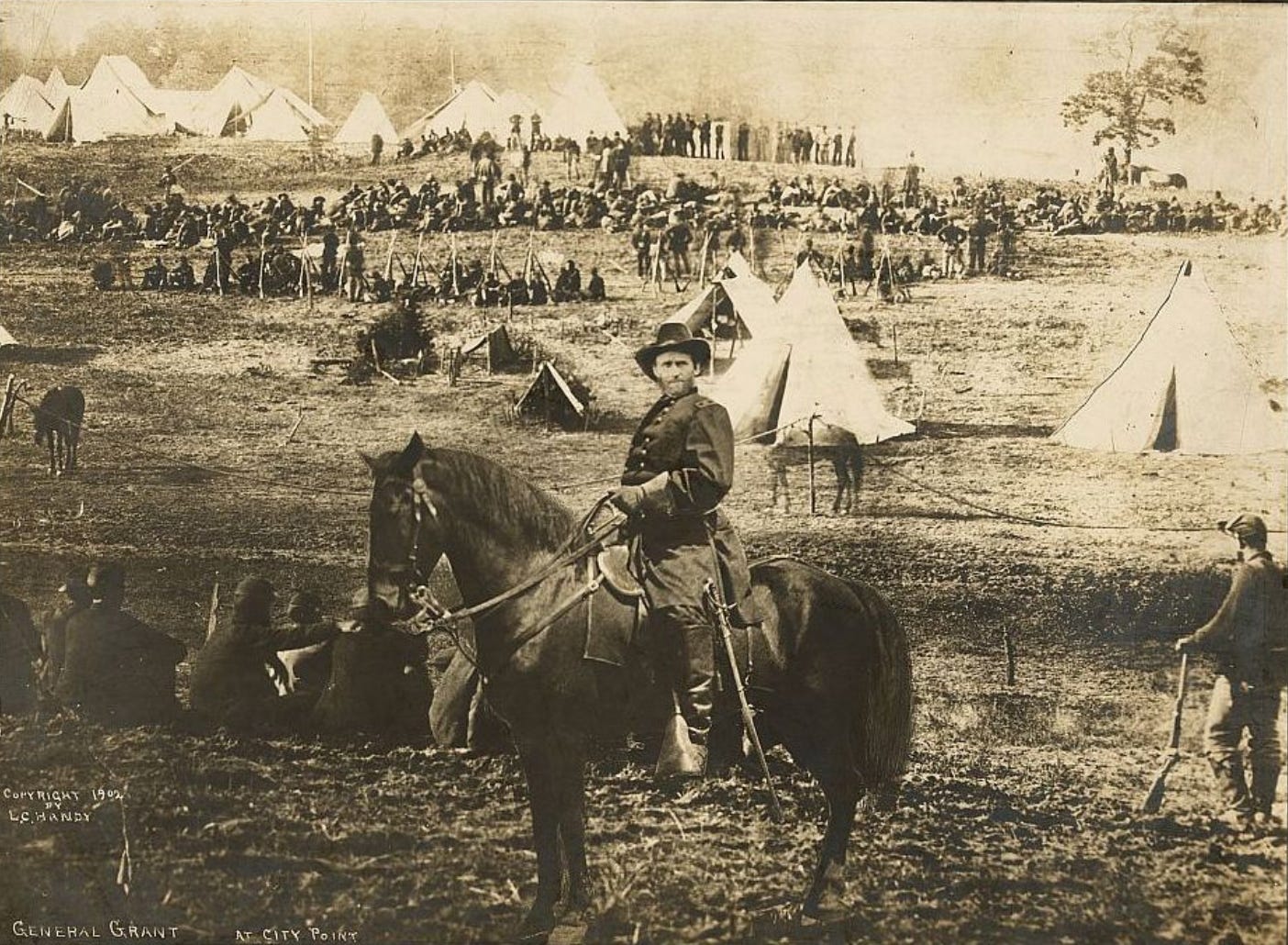

The 1872 election saw the Liberal Republican Party split from their party to oppose Republican President Ulysses Grant’s re-election. The party emerged as the Reconstruction era neared a decade and a growing number of Americans grew anxious to bring an end to it. Supporters also spoke extensively about corruption within the Grant administration.

Horace Greeley, a newspaper publisher and former Representative from New York, was nominated to lead the ticket. Neither the Liberal Republicans nor the Democrats were satisfied with Greeley, who ran a lackluster campaign. As a publisher, he had a long history of writings and opinions for opponents to examine.

Furthermore, he was a longtime opponent of the Democratic Party, leaving many of its voters unenthusiastic about his candidacy. Grant easily won re-election over his unpopular challenger, with 286 electoral votes to Greeley’s 66.

The new party had been launched largely with the priority of ousting the president, and it did not build a coalition capable of producing a long-lasting party. Furthermore, Greeley’s nomination left Americans with a poor first impression of the party and hurt its chances of surviving beyond his campaign.

VIII. The Free Soil, Know Nothing, Constitutional Union, Southern Democratic, and Republican Parties

The 1840s were dominated by the Democratic and Whig parties and were defined by rising tensions between abolitionists and slaveholders.

In 1848, former Democratic President Martin Van Buren split from his party to launch the Free Soil Party. The new party’s top priority was to oppose the expansion of slavery into new western territories. Supporters sought to prevent the situation from growing more fraught.

Van Buren earned 10 percent of the national vote in 1848 and failed to win a single state. The party was short-lived, though when it dissolved in 1854, it merged with another party founded the same year: the Republican Party.

The party of Lincoln succeeded both the Free Soil Party and the Whig Party, which collapsed in 1856. It opposed the expansion of slavery and assailed the institution of slavery, though did not openly support abolition for several years.

1856 saw the Republicans run their first presidential candidate, John Frémont. The American Party, a minor party colloquially known as the Know Nothings, also made their only notable performance in a presidential election. The Know Nothings ran on an anti-Irish Catholic immigrant platform, with supporters often driven by a belief in a Catholic conspiracy to subvert Americans’ liberty.

In the end, former Secretary of State James Buchanan won the presidency with 45 percent of the popular vote. Buchanan and the Democrats ran on a platform that upheld a states’ right to slavery. The new president also made a pledge to serve only one term. The Republicans and the Know Nothings performed laudably for new parties, earning 33 percent and 22 percent of the popular vote, respectively.

During his single term, President Buchanan proved to be ineffective at preventing the nation from descending into civil war, taking little action as southern states seceded in the final months of his tenure. The conditions in which he left the country paved the way for new parties to dominate the 1860 election, including the young Republican Party’s first victory.

As the abolitionist Republicans ascended across America, southern Democrats sought to push the country in the opposite direction. Senator Stephen Douglas, the 1860 Democratic nominee, advocated a policy of allowing a territory to decide for itself whether to allow slavery rather than Congress. The Southern Democratic Party (SDP), a breakaway faction of the Democrats, ran on a platform insisting that slavery was legal in every state and territory.

A fourth party, the Constitutional Union Party (CUP), was formed in 1860 by former Whigs and Know Nothings. The party’s platform was kept limited to keeping the Union together and upholding the Constitution.

Lincoln won the four-way election with just under 40 percent of the popular vote even as he was barred from the ballot in ten southern states. As it turned out, the president-elect from a new party had what it took to see the nation through its darkest era. The young party saw meteoric success in winning congressional seats, jumping from 13 in 1854 to 90 in 1856, effectively replacing the Whig Party.

While they benefited from moving quickly to take the place of the collapsed Whigs, their ability to win seats across government strengthened their position to thrive as a party.

168 years after the party of Lincoln’s birth, Independents and Forwardists should take note of its success in winning races across the country other than the presidency.

Should it follow through on its stated goal of electing hundreds of local Forwardists nationwide and pursue seats in states that have passed voting reform, the party could be well-positioned to build a viable coalition.

IX. The Anti-Masonic Party

During the revolutionary era, American politics were dominated by two parties: the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists (despite President Washington’s warning against forming political parties).

The earliest third party in U.S. history was an anti-elitist, single-issue party opposed to Freemasonry founded in 1828. The Anti-Masonic Party was founded after the disappearance of a former Mason who had become a leading critic of the organization. Supporters of the party feared that the Masonic organization was engaged in secret efforts to manipulate and control the government and undermine the young American Republic.

The party achieved unexpected success in the 1828 elections, winning five seats in the House of Representatives. In 1829, the party expanded its platform to include protectionist tariffs and infrastructure development. Two Anti-Masonic governors were elected in the 1830s: William Palmer in Vermont and Joseph Ritner in Pennsyvania. Anti-Masons also became influential in many state legislatures.

By the mid-1830s, however, the party was splintering. In 1836, they were forced to hold a second convention that rescinded a presidential nomination they had made at a first convention earlier in the year. The Whig Party was also on the rise in the mid-1830s, which had a much broader platform than the limited one of the Anti-Masonic Party.

More and more Anti-Masons abandoned the party and joined the Whigs until the party eventually went defunct in 1840, while the Whigs went on to spend two decades as one of the Republic’s two dominant parties.

Every 20-30 years in America, a third party or independent movement emerges out of dissatisfaction with the two major parties. The only exception to this rule was the trio of left-wing parties that arose in even quicker succession early in the 20th century.

History suggests that 2024 election will bring a similar opening for an alternative to gain influence. Each one of the third parties mentioned in this article prioritized winning a presidential election, and only a handful even sought seats in Congress.

None sought to change our voting system in a way that makes third parties permanently competitive, as Forwardists are attempting with ranked-choice voting (RCV) and non-partisan primaries.

These two changes seek to eliminate the spoiler effect by assuring Americans that their vote will be counted even if the candidate they ranked first loses. A ballot cast for a third party may no longer carry the risk of being wasted if voters are free to rank a major party candidate second. The electoral fortunes of Independents—which make up a plurality of Americans—could rise with an unlocked voting system as well.

Yang has taken a different approach as the new party’s leader. Rather than tying his own political fortune to his party’s, he is encouraging others to join and become leaders of the movement he spearheaded.

The Forward Party’s bottom-up approach will be dependent on a grassroots network of supporters who run for local office and volunteer to promote RCV and open primaries.

The historical timeliness of its launch, combined with its unique approach to third party politics, offers an intriguing roadmap to bring our government back into compliance with the will of the people.

America’s founding fathers sought to create a government that answered to its people, not the other way around.

Our country’s 150-year trend of the periodic rise and fall of third parties suggests that the current moment is the best opportunity Americans will get in the foreseeable future to take on the two-party system that has itself become a chief obstacle to self-governance.

The Union Forward newsletter is published under The Daily Independent: An Independent Report for Independent Thinkers.

Sources

The New Third Party — Andrew Yang

The Biggest Third Party — Forward Podcast

Nonpartisan Primaries — Forward Party Platform

Harry S. Truman and Civil Rights — National Archives

Socialist Party elected officials 1901-1960 — Mapping American Social Movements

Report: NewsNation surveys Biden, economy, crime, 2024 race — NewsNation

First Past the Post Voting: Our Election Explained — Colorado Common Cause

This history is well done, but leaves out one crucial change that had a huge impact in the viability of smaller and newer parties: the elimination of fusion or cross-endorsement voting that state legislatures adopted starting in the 1890s. Before then, the obstacles for a smaller party were much lower--they had to agree on who they wanted to nominate and then circulate ballots with their candidates names on them. Parties printed their own ballots--then candidates won elections based on the total number of votes they received. Fusion is how the Populist Party grew after the Civic War, and it declined as soon as state legislatures--controlled by either Ds or Rs--decided to move to the Australian ballot, which we now refer to as the secret ballot, and they determined how who would get on the ballot, creating severe barriers to smaller parties and favoring the bigger ones. Without fusion (or proportional representation or other vote counting systems like IRV), smaller parties tend to have brief periods of popularity (and that's only when they are elevating a neglected issue that the major parties are ignoring) followed by being seen as spoilers, followed by turning into ballot lines controlled by a mix of ideologues and grifters.

I admire the effort and detail put into this article. Third parties have long existed in the United States, but frankly I find this statement:

"History suggests that the Forward Party will be impactful in the short term"

To be just plain wrong. History suggests the Forward Party will have little to no impact on modern politics. Most 3rd party movements stem from single issues, or from a major party splitting. To use some of your examples:

The American Independence Party in 1968 ran on the issue of "States Rights" (nobody said the issue had to be good). The Party focused on the South, with the intent of capitalizing on regional dissatisfaction with the Civil Rights movement. The same could be said of the Dixiecrat rebellions in years past (where Southern Democrats attempted to prove to their Northern cousins that they needed the South to win: the ultimately proved that the South was unnecessary for the Democratic Party to win).

The Progressive Party in 1912 stemmed from a Progressive Republican (Theodore Roosevelt) challenging his Conservative fellow Republican. Future Progressive Parties (like Robert M La Follette) followed the same pattern: the GOP was a big tent party with many factions. The Progressives consistently felt underappreciated in their own party, and attempted to exert influence by breaking off from the Republican Party, and they had some success! They won some congressional elections, that's not nothing.

Other parties from the 19th century follow a similar pattern. The Republican Party originally formed via a combination of disaffected Whigs (who opposed slavery), Northern Democrats (who also opposed slavery), and Free Soilers. At the end of the day: the GOP absorbed the other minor parties, because the minor parties weren't viable unless they banned together.

The reality is the problem is not the two parties. The problem is the system which governs our elections. The US House operates under a "First Past the Post" Single member district system, the Senate is basically the same thing, and the President is elected separately. In this scenario: the two party system is a natural coping strategy for parties to exert power. Since a party with only 10-20% support is unlikely to gain much power in Congress (or win the Presidency) it makes more sense for those parties to band together in big tents. Unless the Forward Party is proposing to change the underlying structure: it's not offering a solution, it's just a placebo.